Submitted by MNTO Contributor, Hongyu Xiao, for MNTO Gigs

Many Toronto policymakers claim to want more nonprofit or small developers engaged in building housing, and object to the dominance of investors and capital in housing development. Given this goal, one would imagine that Toronto’s land-use planning regime should be geared towards scaling up non-profit housing. However, the opposite is true. As this blog will explore, Toronto’s labyrinthine and burdensome regulations in fact deter nonprofit and smaller developers from getting started in the first place and makes it harder for them to build homes, even when they try. The end result is a system in which only well-connected and capitalized builders have the resources needed to navigate the bureaucracy.

Non-profit and social housing are disproportionately affected by regulatory burdens

A multitude of groups and agencies have listed the main barriers to housing supply in Ontario, particularly development fees, land-use rules, and regulatory uncertainty. Environmental Defence – hardly a pro-corporate organization – has a comprehensive study showing that planning laws, building codes, tax rules, and service charges is one of the most important barriers obstructing the development of mid-rise apartment buildings. It recognizes that these barriers increase the cost of building high-quality, mid-rise apartments, and further that these high costs make it politically unviable for governments to invest in non-market homes.

The latter point is crucial. Regulatory costs are incurred before any homebuilding even starts, so they must be borne until the homes can be sold (which may take years). The more difficult it is to obtain approval, the more upfront capital one must have to even start the development process. In this regard, one common talking point is that regulatory reform is a “giveaway” to large developers. In fact, the opposite is true. Large corporate developers have the resources to hire the staff (consultants, lawyers, and engineers) needed to conduct studies and navigate planning rules, pay fees and taxes, and keep operations running while seeking approvals for projects (which typically take about 32 months). Smaller or nonprofit developers, on the other hand, do not have a capital cushion, and have less capacity to retain engineers or lawyers on their payroll. They have to rely on external consultants to engage in the multitude of studies required by Toronto planning, such as looking at shadow or wind or traffic impacts. This means that smaller projects are disproportionately burdened.

Looking at a few recent projects will make the point clear:

Figure 1: 685 Queen Street West rendering. 9 years and $11 million for 26 units.

1. At 685 Queen Street West, the City spent $11 million and 9 years to build 26 fully affordable units at Riverdale Co-op. $5 million was spent waiving development fees, taxes and charges, and an inordinate amount of time was spent negotiating the approvals process. At this cost of $423,076 per apartment, it will cost the City 16.8 billion dollars to meet the target of 42,000 units set out in the HousingTO 2020-2030 Action Plan. To put this figure into context, this is slightly less than the entire City of Toronto budget in 2024 ($17.1 billion).

Figure 2: 72 Amroth Avenue rendering

Figure 2: 72 Amroth Avenue rendering

2. At 72 Amroth Avenue, the location of the Beaches–East York Missing Middle pilot project, CreateTO spent $631,000 on consultant fees alone to advance Official Plan and Zoning By-Law amendments, for a simple six-story project with 34 units. In other words, the City’s own agency spent more than half a million dollars on external consultants to navigate the City’s own rules. For non-city sponsored projects that do not have a city councilor championing it, the process would be even more lengthy and onerous.

Figure 3: 150 Eighth Street rendering

Figure 3: 150 Eighth Street rendering

3. At 150 Eighth Street, the Canadian Heller Keller Centre is spending $44 million to construct 56 affordable units for members of the deaf-blind community. Even with the City’s Open Doors program, which was supposed to accelerate approval timelines and waive fees, the organization still encountered numerous headwinds from the City. There were numerous requirements, such as the requirement to conduct studies at a cost of $30,000 to identify underground utilities for tree-planting, that inflated costs and made it more difficult for the project to succeed.

These are relatively simple projects – small multi-residential projects with a few dozen units – that should have been absolutely unobjectionable and been supported throughout the planning process. The City had the power to make these projects as-of-right and simplify the approval process. Instead, much-needed housing was blocked, delayed, and watered down. The end result is that construction that costs too much and takes too long, making meaningful scale impossible – instead, we have a smattering of small projects that will barely scratch the housing need. Even if all levels of governments were to increase funding for social housing, more money will not be useful if it is simply spent on navigating the City’s rules.

In addition to explicit costs, land-use rules also impose indirect costs through time and uncertainty. Every month spent obtaining approvals is a month in which housing is not being built, but the organization still needs to pay its staff, operating expenses, and interest on loans. Costs also increase over time with inflation, and federal or provincial funding is often time-limited. Uncertainty is also costly as organizations are required to invest time and money into applications that often require lengthy and expensive modifications, without any clarity that the project will be approved.

We cannot know how many social housing projects are so deterred by these obstacles that they never even get started in the first place. For projects that do get started, one effect of the approvals process is to reduce the number of homes built – for example in the previously mentioned project at 685 Queen Street, the original proposal was for 80 units, which was then negotiated down to 26 units during the planning process. Fifty-four families lost out on affordable housing, when we should have been finding ways to increase the number of units built at lower costs.

Process is not free

All policies have trade-offs. In some instances, such as with health or safety regulations, extra costs are worthwhile as they involve essential building elements that should not be compromised. However, many of Toronto’s land-use rules are not about addressing the needs of the people who will actually live in the housing, but are aimed at meeting psychological or aesthetic needs, often on dubious grounds. A clear example of this process are policies requiring minimal net shadow. There is no objective metric that demonstrates how shadows are harmful, and people can reasonably differ on the appeal of shadows. Nevertheless, Toronto planning requires all homebuilders to engage in shadow studies and spend time and money addressing shadow impacts. Buildings that have to contort themselves to meet Toronto’s shadow guidelines, often with a “wedding cake” structure), are more expensive and harder to build.

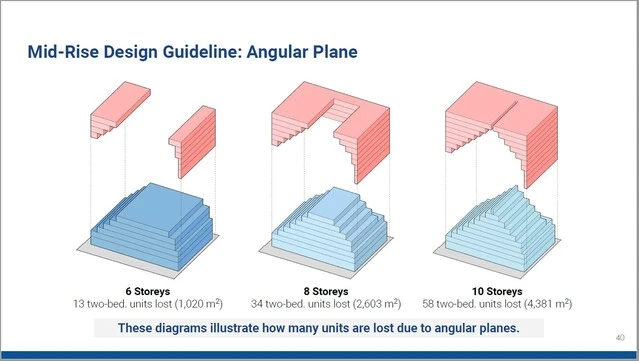

Figure 5: Angular plane requirements reducing the number of homes. Source: Ryerson University Planning Group 720, 2021

Figure 5: Angular plane requirements reducing the number of homes. Source: Ryerson University Planning Group 720, 2021

Even assuming that shadows are negative, those harms are totally outweighed by the harms of high rents or nonexistent housing. A further issue with these rules is that many of them are either subjective, such as the need to conform to “neighborhood character,” or based on arbitrary considerations, such as setback and separation guidelines based on theories about the “ideal” distance between buildings. Subjective guidelines add to uncertainty and require expensive studies to address their concerns, while rules about setbacks and tower separation reduce the usable area of a plot of land, making the per unit cost more expensive.

Toronto’s planning rules are replete with requirements like these that while on their own may appear benign or easy to meet, cumulatively represent a burden on homebuilders that make housing construction costly and lengthy. Addressing the total weight of these burdens is necessary if we want to see social or non-market housing thrive at scale. Reform can be effective – Los Angeles tripled the amount of affordable housing in development in 13 months after it set a rule that as long as a project is 100% affordable and meets a basic set of criteria, it must be approved by the planning department within 60 days. This was accompanied by a California-wide “density-bonus” that allowed developers of 100% affordable housing projects to exceed local zoning laws. For-profit developers used the law to build tens of thousands of affordable homes, at no extra cost to the taxpayer. Developers even scrapped “luxury” apartment projects entirely, re-submitting the plans as 100% affordable housing.

Getting to “yes” instead of finding ways to say “no”

It is time for Toronto Planning (and by extension, Council) to ask itself what it wants to achieve. If the goal is to maximize the amount of housing available, particularly social or nonmarket housing, then its rules and processes should be directed towards achieving this goal. Instead of finding ways to say no to housing, let us find ways to say yes.