By: More Neighbours Toronto (Written by: Eric Lombardi, Bilal Akhtar, Sushil Tailor, and others)

The San Franciscoization of Toronto continues unabated as our city becomes an exclusive urban playground for the wealthy. A labyrinth of archaic rules, exclusionary zoning laws, slow processes, and a culture of selfish anti-growth NIMBYism have suppressed Toronto’s ability to build enough housing for its aspiring population, sending prices and rents into the stratosphere far beyond what most of us can afford.

It might come as a relief for some to learn that Toronto’s City Council has passed a new policy on Inclusionary Zoning, which has the potential to help alleviate or accelerate the ongoing housing crisis. As proposed, it would require new housing developments near rapid transit to designate 5% of units as below-market affordable housing, which would gradually increase to 8-22% by 2030 depending on location. While to some this approach may be cautious, the overwhelming desire for action led to some city councillors backed by well-intentioned activist organizations to call for a faster phase in and a 20-30% target for affordable units by 2030.

So why not? It sounds perfect: more affordable housing, at almost no cost to the taxpayer. Only those greedy developers building soulless glass skyscrapers would pay. Except for the fact that they won't.

The consequence will be fewer homes built, and fewer affordable units paid for exclusively by new buyers, sending already prohibitively expensive costs for housing even higher as supply tightens. Toronto will cement its status as a city for the wealthy and those lucky enough to qualify-for and win the affordable housing lottery, the new NIMBY-approved Canadian Dream.

If we want Inclusionary Zoning to succeed, as every Torontonian should, we need to change our housing policies to create abundant, available, and attainable housing options in every neighbourhood. We must build greater quantities of affordable and market-rate multifamily housing everywhere, not just on avenues, polluted transportation corridors, or former industrial sites. We cannot see marginally higher affordability percentages at major transit station areas as wins on their own. People cannot live inside of a percentage.

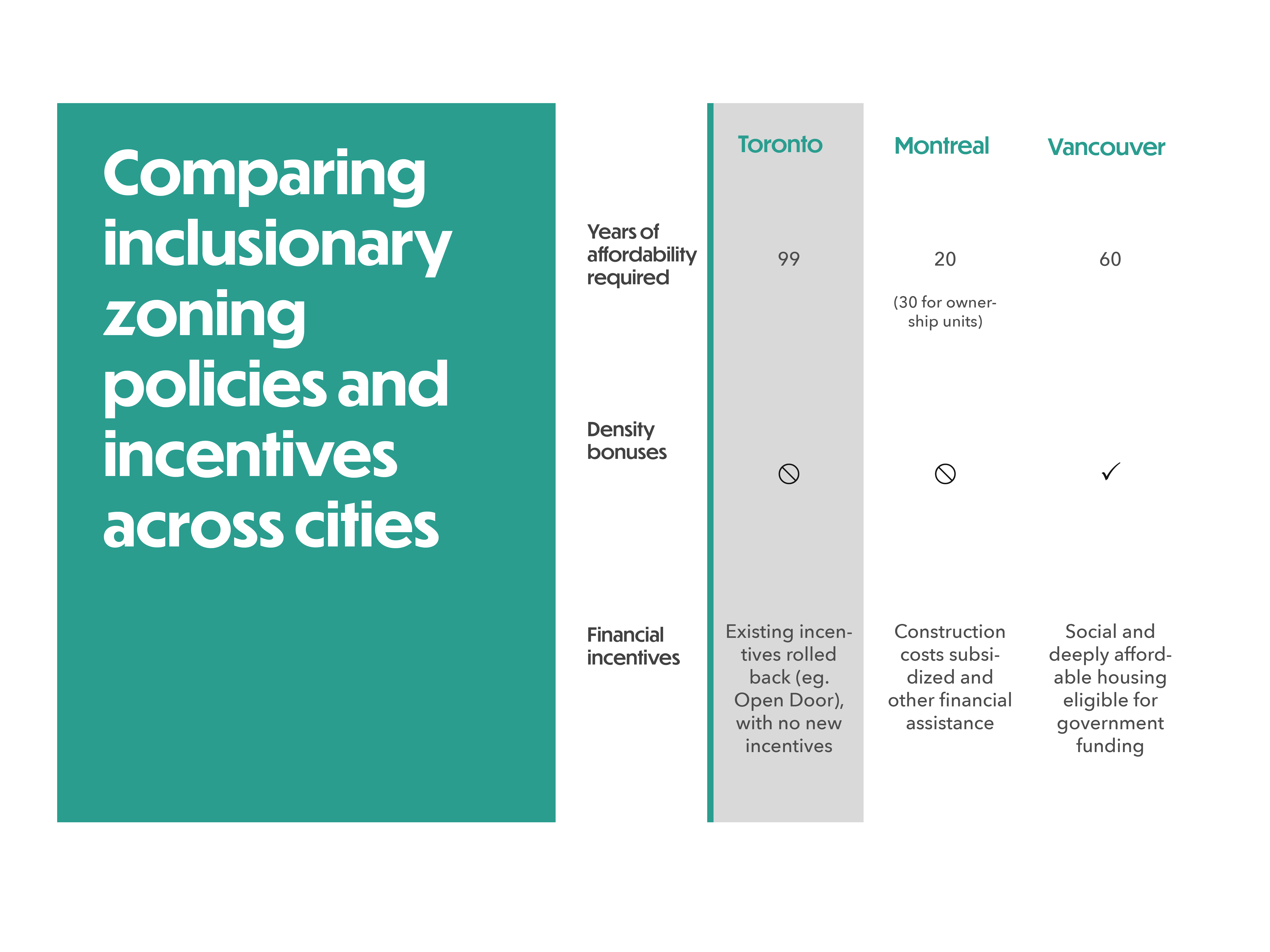

In other cities, Inclusionary Zoning policies have been paired with policies that offset the burden of heightened affordability targets by making it easier to build housing. These include density bonuses, fee waivers, relaxed urban design guidelines, limited public consultation processes, expanded as-of-right approvals, and direct financial incentives. These rules make it possible for developers to build denser, faster, and with greater efficiency from scale. The outcome is more affordable housing and more market-rate housing for the city, an outcome Toronto should aspire to.

Unfortunately, Toronto is offering few incentives to encourage developers to build more homes; it is not even extending existing ones, such as the Open Door program. This risks decreasing or delaying construction in a city where 135,000 people are already underhoused and many more leave as they become priced-out.

Many anti-growth councillors favour higher affordability targets for inclusionary zoning because it puts a progressive facade on the typical exclusionary agenda prized by wealthy homeowning constituents. They don’t want Inclusionary Zoning to succeed in making housing more affordable, because failure is the point.

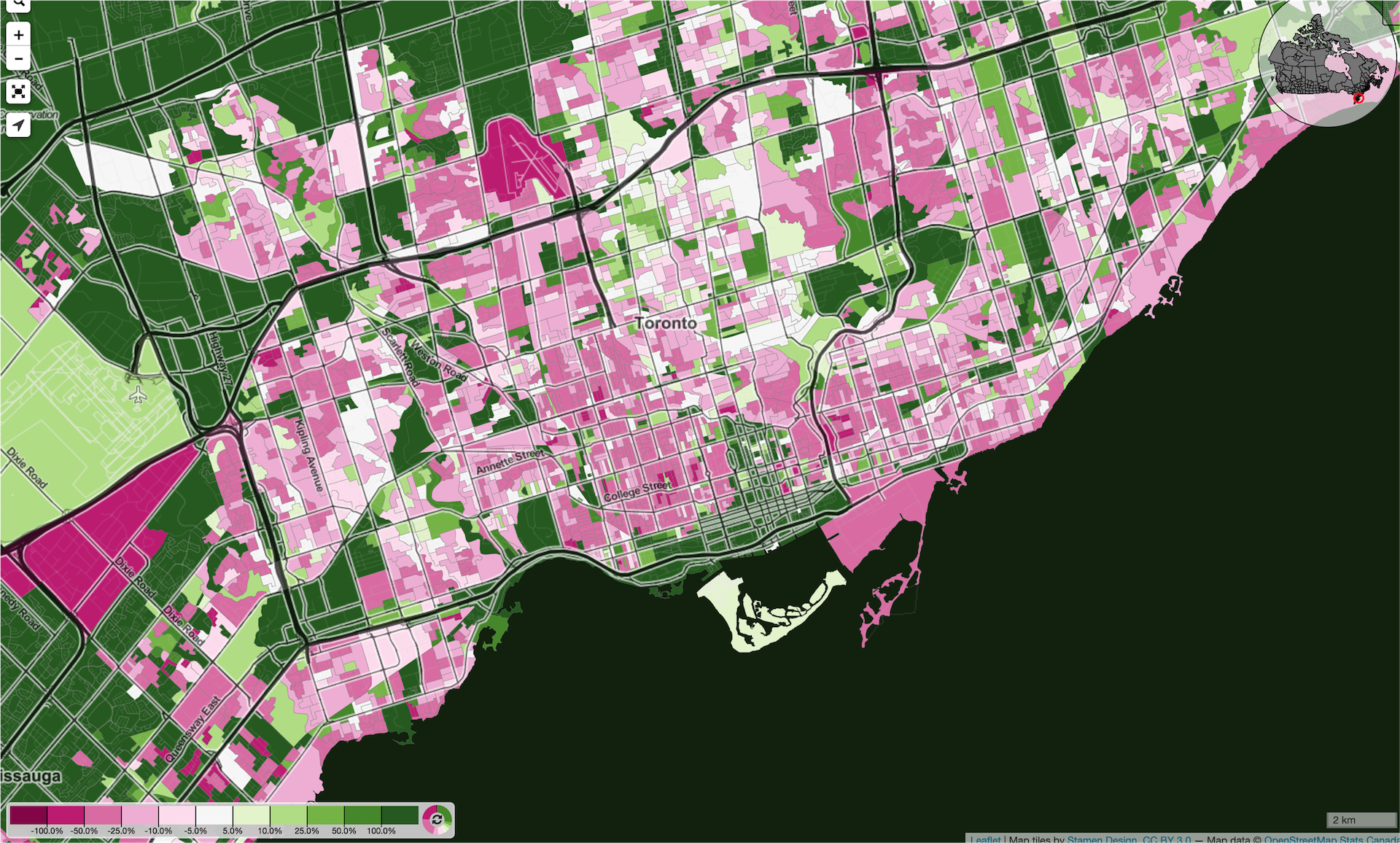

If Council is serious about Inclusionary Zoning, it must end exclusionary zoning, wherein the city protects 65% of Toronto’s residential land for detached homes typically geared to single-families. These greedy policies have been championed by small but well organized homeowner groups that prioritize their shallow interests by bullying local politicians to fight new housing. This forces overdevelopment onto the remaining small parcels of land. Should we cheer on councillors who want to make those small parcels of land more inclusionary, while suspiciously making wealthy neighbourhoods like the Annex, Lawrence Park, and Leslieville more exclusive?

Eating into developer profits is politically popular, but if it leads to fewer housing completions and fewer affordable housing units than otherwise, has anything really improved?

Toronto’s inclusionary zoning legislation is an important first step in building a great city accessible to people of all classes and income levels. It is the tip of the spear in Toronto’s effort to correct a generation of classist, ageist, and environmentally unsustainable housing policy. But it isn’t enough in isolation; to be successful, we must bring an end to exclusionary zoning because we need more housing, affordable and market-rate, for rent and for ownership, in every neighbourhood.